Populations

CHILD BIPOLAR - PART II

CHILD BIPOLAR - PART II

Child bipolar is basically adult bipolar at an eariy age, but special attention needs to be paid to certain features.

by John McManamy

Child bipolar is basically adult bipolar at an eariy age, but special attention needs to be paid to certain features.

by John McManamy

I RECALL attending a session on child bipolar at the Fourth International Conference on Bipolar Disorder in 2001 and hearing one panelist mention that we would never have even contemplated having this type of discussion just a short while ago. That's how fast things had changed.

Enter Barbara Geller

At the conference, Barbara Geller MD of Washington University (St Louis) presented two-year study findings that showed child-onset mania is not just a milder version of the adult variety. The ongoing study of 268 kids compared 93 kids who experienced mania to those with ADHD and a population of controls.

Most of the kids in the study had mixed mania or psychotic episodes, 87 percent rapid-cycled, usually continuously, some for three years, with a poor prognosis over 18 months. The mean age at study entry was 11 years. Mean age of onset was seven years, with the kids ill for three years. Less than half had been given an antimania drug. Almost no one had recovered after six months. After 18 months, half had recovered, and after 24 two thirds, but half of these relapsed. In families with high maternal warmth, 42 percent of the kids relapsed vs 100 percent in families with low maternal warmth.

"A seven-year-old manic child," Dr Geller concluded, "is sicker than a 20-year-old manic adult."

Three years later, tracking these same kids, Dr Geller in the Archives of General Psychiatry reported that: "Chronic, severe symptoms have been reported in about twenty percent of adults, but were seen in most" of the kids in the study.

By 2008, half of the kids in the study had matured to adulthood, allowing Dr Geller in the Archives to make this observation:

In grown-up subjects with child BP-I, the 44.4% frequency of manic episodes was 13 to 44 times higher than population prevalences, strongly supporting continuity between child and adult BP-I.

This bears special emphasis: The kids Dr Geller had classified as bipolar in her study are maturing into adults with a no-brainer bipolar diagnosis. Back when I interviewed Dr Geller soon after the release of her initial study findings in 2001-2002, she had strongly cautioned me that we did not know if these kids would grow up to have bipolar as adults. Indeed, she continued, there was no study data on this question available anywhere. Now we know.

It is significant that when Dr Geller was setting up her study in the mid-1990s the kids she classified as bipolar had experienced or were experiencing first episode mania according to strict DSM-IV criteria (including the one-week time minimum). In addition, Dr Geller zeroed in as her selection criteria at least one of two "cardinal symptoms" of mania - elation and grandiosity.

SIGN UP FOR MY FREE EMAIL NEWSLETTER

A number of mania features - distractibility and hyperactivity - overlap with ADHD, so Dr Geller avoided including kids in her bipolar group only based on these type of symptoms. This also meant that kids who simply showed signs of irritability and aggression were weeded out of her population, as these traits tend to be "ubiquitous ... across child psychiatry diagnoses."

Significantly, later on Ellen Leibenluft of the NIMH would investigate this irritable sub-manic population, setting the scene for an entirely new diagnosis - not child bipolar - that truly can be regarded as controversial. Hold that thought ...

What the Hell is Child Bipolar, Anyway, and What Does It Look Like?

Meanwhile, Demitri and Janice Papolos, authors of the surprise 2000 best-seller, The Bipolar Child, had set up the Juvenile Bipolar Foundation and were zeroing in on a "core phenotype" for child bipolar. Joseph Biederman and his group at Harvard were similarly engaged. Likewise, Dr Geller was coming up with key observations based on her group of kids. Other investigators were adding their own two cents.

On one hand, there appeared to be a lack of consensus in the field. On the other, it required little effort to reconcile disparate views into a rough guide everyone can pretty much agree on. Key points:

Severity: In 2001, Martha Heller, then executive director of the Child and Adolescent Bipolar Foundation, with a perfectly straight face told a session at the Fourth International Bipolar Conference that a child bipolar diagnosis need only include a yes to this one question: Has your child ever tried to jump out of a moving car?

In other words, if it's close to normal - it's probably normal. If it scares the shit out of anyone within the kid's blast zone, it may be bipolar. It may be something else equally severe, but let's make one thing perfectly clear - severe can never be mistaken for normal.

Mania: The type of normal kid behavior that drives parents crazy may be difficult to distinguish from various forms of mania, but beleaguered parents invariably report raging "mixed" states in their kids that typically go on for hours at a time, without letup. This type of behavior, in turn, may be difficult to distinguish from conduct disorder or other types of disruptive behavior. Likewise, mania may be difficult to separate out from ADHD, particularly when overlapping symptoms are involved. Helpful hints below ...

Cycling: Cycling is the defining feature of bipolar, whether we are talking about mood, thoughts, energy levels, or sleep (invariably all of them together and not necessarily in phase). Rapid, slow, or glacial, whether in kids or adults, what goes up must come down. Kids tend to be extremely rapid-cyclers, often lurching up and down at least once during the course of the day, but in a surprisingly predictable pattern. Parents report their kids as sluggish in the morning, with the rocket thrusters going off in the afternoon. Once lift-off has occurred, there is no bringing them back to earth. Unlike "normal" disruptive behavior or conduct disorder or ADHD, which may let up in say 20 or 30 minutes, entire families are literally held hostage for hours.

Ironically, many of these kids cycle in and out far too rapidly to meet the minimal DSM time requirement for mania (one week). In this instance, it may be helpful to think of the pattern of cycling as one continuous mixed manic episode. Regardless, the cycling is a dead give-away.

Elation/grandiosity: Parents typically report kids as being "too big for their britches." One example provided by Biederman and Wozniak is a kid digging up the backyard to plant a garden to feed the starving people of the world. It is normal, Dr Geller advises, for a child to be super happy at Disneyland. An example of pathological elation, on the other hand, she goes on to say, involved an eight-year-old girl being super infectiously happy during a clinic visit for failing grades at school.

Elation and grandiosity were the cardinal symptoms Dr Geller used to separate out the bipolar kids from the ADHD kids in her study. Add risk-taking and anger to the mix, as Dr Papolos does, and we are talking about kids who are not merely careless and inattentive.

Severe sleep disturbances: This is tied into cycling and circadian rhythm disruption. Bipolar kids (like a lot of bipolar adults) have issues getting to bed at a normal hour. Moreover, these kids tend to experience a whole range of complications, including "night terrors." Herculean does no justice to the effort involved in getting these kids up in the morning and ready for school.

Depression: Children will switch in and out of depression, irritable mania with explosions, and euphoric mania throughout the day, almost every day.

Family history of bipolar: This may prove to be the diagnostic tie-breaker.

More on the ADHD-Mania Distinction

Nearly all kids under age 12 who meet criteria for mania also meet criteria for ADHD. But the reverse is not necessarily true, Biederman and Wozniak report. In their clinic, 79 percent of the referrals there met criteria for ADHD without mania. If ADHD rating scales are used, a manic child and a child with ADHD cannot be distinguished from each other. The Mania Rating Scale, on the other hand, can identify manic children. Manic children, they report, generally have "greater psychopathology and poorer functioning."

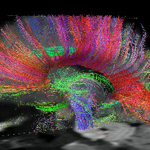

At a symposium at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting in 2009, Dr Biederman, with the aid of brain scans, illustrated that while ADHD essentially involves deficits in the thinking part of the brain, bipolar involves deficits in the emotional part of the brain. It's a lot more complicated than that, Dr Biederman made clear (as thinking deficits can result in runaway emotions while emotional deficits can result in confused thinking), but a picture is beginning to emerge.

Other Considerations

Like adults, most kids with bipolar have major anxiety issues. Also, like their adult counterparts, these kids have difficulty with a range of cognitive functions. Add to that the simple fact that even normal kids have difficulty modulating their emotions. Taken together, on top of their bipolar, each day in the life of a bipolar kid poses a major challenge. These boys and girls are easily stressed, overloaded, overwhelmed, unable to cope, forced to tiptoe through booby-trapped environments seemingly structured for the specific purpose of making them fail.

Not surprisingly, these kids are prone to melting down. Or they may shut down. Typically, it's both, often in rapid-fire sequences. For the parents there is no let up. Under siege at home, they are called into school on a moment's notice. Meetings, appointments, hearings, on and on and on, all consuming, to the point that the other kids in the family take a distant second place. No life of one's own. That's the way it is, a day in the life ...

Go to Child Bipolar Part III ...

Previous article: Child Bipolar Part I

This article replaces a series of earlier articles, Jan 24, 2011, reviewed Dec 4, 2016

NEW!

Follow me on the road. Check out my New Heart, New Start blog.