Recovery

THE HAPPINESS CHALLENGE

THE HAPPINESS CHALLENGE

IN JULY 2009, on my blog, Knowledge is Necessity, I ran a poll asking readers how their last seven days went. What a miserable bunch we turned out to be. Only three in a hundred replied, "couldn't have gone better." while only one in five (23, 18%) said the last seven days went "pretty well."

By contrast, seven times as many (28, 22%) told me ther week "totally sucked" while one in four (31, 24%) reported the week "posed a serious challenge." Filling in the middle, one in three of (41, 32%) reported that the last seven days "had its ups and downs."

Maybe we're simply not meant to be happy, and the sooner we acknowledge this the happier we'll be. Maybe our perception of happiness is totally wrong, and we become miserable chasing after the wrong things. Maybe life is all about successfully negotiating its special challenges, instead. Maybe the best we can hope for is quiet acceptance.

One of my readers, Louise, offered this explanation. "Rarely," she said, "do we experience events that we think are our peak experiences in life. By contrast:

"Totally sucked" events are as common as rain. People die tragically. People die from totally normal reasons like old age. Spouses leave you for someone else. Your company is bought out and half the workforce fired. Stocks plummet (goodbye retirement!) Children total your car.

I think Louise is onto something here. If we invest our happiness in seldom-occurring peak experiences we are setting ourselves up for endless rounds of disappointment. The trick to managing life, then, is how well we handle those "common as rain" let-downs and total bummers.

George Vaillant and the Grant Study

It turns out one man has been on the case for the last four decades. A feature article, by Joshua Shenk in the July 2009 Atlantic Monthly, "What Makes Us Happy," explains:

In 1937, what was to become an epic longitudinal study was launched. The study would follow the lives of a cohort of Harvard men (including JFK). The original funding came from department store magnate WT Grant, and hence became known as the "Grant Study."

Harvard psychiatrist George Vaillant took over the Grant Study in 1967 when it was on life support, and kept it going another 42 years. According to Shenk:

[Valliant's] central question is not how much or how little trouble these men met, but rather precisely how—and to what effect—they responded to that trouble. His main interpretive lens has been the psychoanalytic metaphor of 'adaptations,' or unconscious responses to pain, conflict, or uncertainty.

For instance, as Shenk describes it, when we cut ourselves, our blood clots, but a clot may also lead to a heart attack. Similarly when we encounter a life challenge - large or small - our defenses "float us through the emotional swamp," ones that can spell redemption or ruin.

An unhealthy response such as psychosis may at least make reality tolerable (but at what cost?), while "immature adaptations" include various form of acting out (such as passive-aggression). "Neurotic" defenses such as intellectualization and removal from one's feelings are quite normal.

Healthy (mature) adaptations include altruism, humor, anticipation, and other behaviors.

According to Mr Shenk:

Much of what is labeled mental illness, Vaillant writes, simply reflects our 'unwise' deployment of defense mechanisms. If we use defenses well, we are deemed mentally healthy, conscientious, funny, creative, and altruistic. If we use them badly, the psychiatrist diagnoses us ill, our neighbors label us unpleasant, and society brands us immoral.

As the Harvard men grew older, they increasingly favored mature defenses over immature ones. As well as healthy adaptations, other reliable indicators for happy lives included education, stable marriage, not smoking, not abusing alcohol, some exercise, and healthy weight. As Shenk puts it:

Of the 106 Harvard men who had five or six of these factors in their favor at age 50, half ended up at 80 as what Vaillant called "happy-well" and only 7.5 percent as "sad-sick."

Those who had three or fewer protective factors were three times as likely to be dead at 80 as those with four or more factors.

And this sobering finding: "Of the men who were diagnosed with depression by age 50, more than 70 percent had died or were chronically ill by 63."

SIGN UP FOR MY FREE EMAIL NEWSLETTER

Ironically, according to Vaillant, positive emotions make us more vulnerable than negative ones. Whereas negative emotions tend to be insulating, positive emotions expose us to rejection and heartbreak. Perhaps, then, it takes a brave individual to be happy. Perhaps happiness does not elude us so much as we elude happiness.

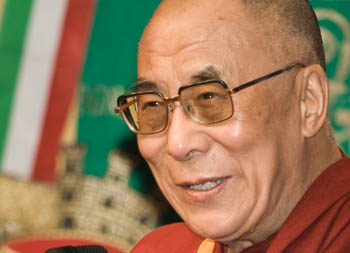

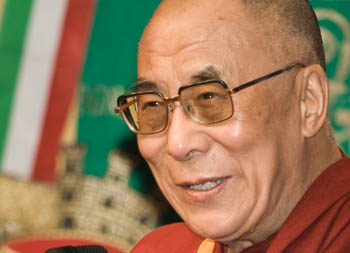

The Buddha and the Dalai Lama

We suffer. That is the Buddha's First Noble Truth. And virtually every minute of our lives we manage to prove the Buddha right.

Buddhism has a special appeal to me. It's all about acknowledging reality, but with special emphasis on skillful living in order to achieve happiness, real happiness, not just fleeting pleasure. As the Dalai Lama and Howard Cutler explain in their classic 1998 book, "The Art of Happiness", "the purpose of our existence is to seek happiness."

On the face of it, this seems like a selfish "me-first" approach, totally out of phase with basic Buddhist precepts such as ego-lessness, but no: "Survey after survey has shown it is unhappy people who tend to be most self-focused and are often socially withdrawn, brooding, and even antagonistic."

By contrast (and validating Vaillant), happy people "are generally found to be more sociable, flexible, and creative and are able to tolerate life's daily frustrations more easily than unhappy people." And, most important, "they are found to be more loving and forgiving than unhappy people."

It's easy, really. We're unhappy because we excel at all the stupid people tricks. We're attached to our own idiotic desires and fears and anxieties. We can't let go. We become invested in our delusions. We worry about the wrong things and fail to pay attention to the things we are supposed to be paying attention to. But worst of all, we become wrapped up in ourselves.

The Dalai Lama's message is simple: We get over ourselves by paying attention to others. We signal a willingness to put their needs before ours. We cultivate loving kindness. Next thing we're establishing connections and intimacies. Next thing, we're not as absorbed in our own destructive thoughts and feelings. Next thing we're not alone. Next thing, maybe, there are periods in our life where we are experiencing happiness.

Yes, But Aren't There Times When We Need to Put Ourselves First?

One of my readers, "Jane," at HealthCentral's BipolarConnect was absolutely correct in responding that, "sometimes MY needs do have to come before someone else's." She mentioned her daughter, who is much happier now that she stood up for herself instead of passively submitting to her husband's demands.

Of all things, as I was having this dialogue with Jane, I had just cut a certain toxic individual out of my life. Good riddance to her - I'm no doormat, but now what? At the time, I was nursing some open festering psychic wounds, which was causing my brain to lock into disturbing thoughts and not let go. The Buddhist practice of cultivating detachment is good for this sort of thing, but I am not that far along the road to Buddhahood. Neverthess, I did have the presence of mind to recognize these thoughts for what they were - just thoughts, only possessing power when I allowed myself to become attached to them.

So my challenge was not to carry over any ill feelings from my association with this individual to other people in my life. The bottom line is no one likes being around people with their unresolved crap on display. Thus, even though this individual could no longer be in my life, I still needed to be thinking about her with a sense of fondness and goodwill. She deserves at least that much. Then, I would be in a better position to project a more positive attitude to others.

I don't claim to be good at this. I'm only stating what I needed to do. Otherwise, I was going to be a very lonely and unhappy for a long time.

Sometimes, I look up at the sky and talk, kind of the way Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof talked with God. Of course, both God and the sky have a way of remaining silent - or at least it seems that way. When I arrived home from talking to the sky, I happened to open "The Art of Happiness" to this:

So let us reflect on what is truly of value in life, what gives meaning to our lives, and set our priorities on the basis of that. The purpose of our life needs to be positive. We weren't born with the purpose of causing trouble, harming others. For our life to be of value, I think we must develop basic good human qualities - warmth, kindness, compassion. Then our life becomes meaningful and more peaceful - happier.

In the course of their collaboration on "The Art of Happiness," Howard Cutler had a chance to witness the Dalai Lama in action, close up. In the book, he reports a series of exchanges during a stay at a hotel in Arizona. It started out with the Dalai Lama on his way back to his room with his entourage. One of the housekeeping staff was by the elevators. The Dalai Lama stopped, greeted her, and engaged her in conversation, asking about her. He left her in a state of pleasant surprise.

Same time next day, same place, there was the housekeeper, this time with a companion. Next day and the next - housekeeper, more companions - until by the end if the week, "there were dozens of maids in their crisp gray-and-white uniforms forming a receiving line that stretched along the length of the path that led to the elevators."

Happiness - It's not an indulgence. It's life's greatest challenge.

On to: Happiness - Putting in the Effort

Published as a series of blogs 2009-2010, reworked into a series of articles Jan 26, 2011, reviewed Dec 5, 2016.

NEW!

Follow me on the road. Check out my New Heart, New Start blog.