Treatment

MEDICAL MARIJUANA FOR BIPOLAR

MEDICAL MARIJUANA FOR BIPOLAR

It may be just what the doctor ordered, but can we trust ourselves?

by John McManamy

It may be just what the doctor ordered, but can we trust ourselves?

by John McManamy

MEDICAL MARIJUANA is something of a misnomer. A physician does not write a prescription for a specific compound at a specific dose that a patient fills at a pharmacy. Indeed, the physician’s only involvement may be in issuing the requisite medical marijuana card.

The card simply allows users to shop at marijuana dispensaries.

The case for Medical Marijuana

Like most other psychiatric meds, marijuana slows down the brain. Depending on the user, this may translate to relieving anxiety, reducing stress, regulating sleep, easing mania and agitated depressions, and even improving cognition. For some people, marijuana may offer a safer alternative to prescription meds. But there is a major catch or two ...

Safety and Abuse Issues

Every medication carries risks, and marijuana is no exception. "Self-medicating” is an extremely serious concern for our population. Six in ten of those with bipolar have experienced substance abuse sometime during their life, five times the rate of the general population. Co-occurring substance abuse can effectively turn treatable bipolar into untreatable bipolar.

In addition, a number of studies have linked marijuana use to an increased risk of psychosis. This is not the same as saying marijuana “causes” psychosis. Moreover, the studies suggest that the risk is greatest in those who begin marijuana in their teens. Nevertheless, we need to be mindful of the possibility.

And it goes without saying: Cognitive abilities take a major hit (pun intended). Last but not least, smoking marijuana raises the same health concerns as smoking tobacco.

An Alcohol Parallel

“Glass of wine a day may ward off depression,” reads a headline on WebMD.

The catch is when that one glass of wine turns into two or three - when a small indulgence turns into a craving and an addiction, when an escape from stress turns into an escape from reality, when an enhanced ability to function turns into a major impairment and a ruined life. In other words, as with alcohol, can we trust ourselves with marijuana?

Efficacy Issues

There are no clinical trials to support the use of marijuana in treating bipolar. Having said that, “absence of evidence” does not equate to “evidence of absence.” Nevertheless, we lack essential medical guidance in terms of best practices and treatment strategies.

Two Possible Marijuana Strategies

The first strategy is analogous taking an anti-anxiety med PRN, “as needed.” In an ideal situation, the med does its job and life returns to normal. We stop taking the med before building up a tolerance or dependency or incurring long-term side effects.

The second is analogous to staying on a mood stabilizer as part of a maintenance strategy, perhaps not continuously but on a more regular basis. In an ideal situation, the med is running in the background. We are hardly aware of it.

It is very important to note that neither strategy calls for getting high. A “medical” dose is not to be equated with a recreational dose. Likewise, a medical bipolar dose (whatever that may be) is not to be equated with a dose for another medical condition, such as chronic pain.

To put it another way: Getting high is not a sign of the efficacy of the treatment. Nor is it a legitimate side effect. The result you’re looking for is extremely subtle but profound - a brain that works. Nevertheless, some short-term cognitive impairment may be inevitable. As with any medication, this needs to be incorporated into your treatment strategy, such as, perhaps, using only before bedtime.

Please endeavor to find a physician or therapist you can work with. If you are on any medication, you need to inform your physician.

Choosing Your Product

All marijuana plants are technically cannabis sativa. But there is an indica variety that has the effect of slowing down the brain, as opposed to the more uplifting effects of sativa. As a general rule, sativa may help more with depression, indica for a runaway brain and regulating sleep.

Dispensaries supply clearly labeled products, but there is plenty of room for confusion. There are also various blends and hybrids.

Doses and Delivery Systems

The main concern for medical marijuana, especially for bipolar, is calibrating doses. Back in the old days of nickel bags and marijuana brownies, this was virtually impossible. These days, dispensaries carry very sophisticated products that promise some degree of consistency. But we are still in a wild west market.

Ingestible cannabis - Typically, it takes 30-60 minutes to feel the effects of ingested cannabis. The effect also tends to be longer lasting. Accordingly, ingestibles may lend themselves to maintenance strategies. A very little goes a very long way.

Inhaled cannabis - The effect is instant and more transient, which lends itself to “as needed” strategies. Inhaled cannabis is far less potent than the ingestible variety, but one hit may be all you need.

Vaporizers and pens - In their latest incarnation, these are e-cigarettes applied to marijuana. Depending on the pen, the user inhales the vapor of a concentrate or flower, without the health risks of traditional smoking. Because no lighting up is involved and because there is little or no telltale aroma, users can take a discreet hit with little fear of discovery.

SIGN UP FOR MY FREE EMAIL NEWSLETTER

Lest there be any misunderstandings ...

Please do not construe any of the above as an endorsement for using marijuana to treat your bipolar. Nor should any of the above be interpreted as any kind of medical or consumer guideline. Rather, we are seeking an intelligent discussion on an issue that is fraught with ignorance and lack of understanding.

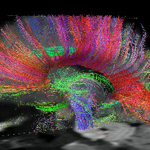

The Endocannabinoid System

Endocannabinoids (ECs) are naturally occurring compounds throughout the brain and body that regulate cellular signaling and cellular maintenance. They function in a similar fashion to neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine, except they travel backward, against the flow, from the postsynaptic cell to the presynaptic cell.

At the presynaptic cell, the ECs dock to CR1 and CR2 cannabinoid receptors and release their chemical messages. One of the effects may be to inhibit the release of certain neurotransmitters from the presynaptic cell back to the postsynaptic cell.

The effect is to keep numerous systems in the body and brain in a state of homeostasis (equilibrium). This may translate into neural circuits not getting overwhelmed by excitatory neurotransmitters such as glutamate (which has been fingered in bipolar).

To give a parallel, in appetite regulation, it is believed that ECs play a major role in “energy homeostasis,” in part by encouraging the growth of fat cells. A system this widespread and so involved in maintaining balance in so many different biological processes is hardly one we want to lightly tamper with. Hence, the concern over recreational marijuana use, particularly in the young when the brain has yet to complete its process of development.

But scientists are quick to note that the endocannabinoid system begs the need to develop specially targeted medical interventions – from Parkinson's and Huntington's to neuropathic pain, as well as mood and anxiety disorders.

Unfortunately, because cannabis is classified as a Schedule One controlled substance by the FDA, we know next to nothing about these possibilities. Depending on what source you read, there are some 60 to 100 different cannabinoids in the marijuana plant. These are chemical cousins of the endocannabinoids found naturally in the brain and the body. The most well-known is THC, which is the psychoactive agent in marijuana. But the other cannabinoids may account for some of the therapeutic benefits, plus a host of unknown ones. There may well come a day when doctors prescribe “smart cannabinoid” meds, specific agents targeted to achieve specific results for a specific condition. In the meantime, we have do-it-yourself “medical marijuana.”

A Patient's Experience

On HealthCentral, one of my readers – let's call her Jane – reported on her use of medical marijuana.

She has smoked or ingested or inhaled vaporized marijuana for a good long while. She has also been on psychiatric meds. A year before, she went off the marijuana to see how she would do.

The results were not at all good: “Hypomania/mania with poor decision-making. Functionality decreased, mixed states intermittently.” Plus bad sleep.

Seroquel turned her into a zombie and needed to be stopped. She expected her cognitive function and memory to improve, but she thinks the Effexor and Klonopin and Abilify she is on had a major role in that not happening.

As Jane described it: “It sucked. It truly sucked.” Time to get back on the marijuana. With her psychiatrist in the loop, she started taking an ingestible dose of an indica variety every day at 9 PM. Results: “A balance has been found.”

Jane reported an “incredible” decrease in mania and hypomania and poor decision-making. Her motivation, though, is down, which she and her psychiatrist were trying to figure out. Her guess is that maybe the motivation she experienced in mania/hypomania was not her true normal. This, she says, is the only drawback.

Her short-term memory is no worse off. More important: “A sense of well-being has returned to my life. I am OK. Even my psychiatrist is pleased. He'd never admit it though - sigh.”

It is clear from Jane's account that her intent is to settle her over-active brain rather than get high. Had she taken the drug in the morning, she may have felt too cognitively slowed down to adequately function. An evening dose is a different story.

When she wakes up, she most likely feels - more accurately, she hardly feels - the residual effects of the ingestible indica still in her system. These residual effects seem to equate to a clinical effect that works for her. She can face the day with a quieter brain.

Okay, before you get a medical marijuana card and rush down to the dispensary: Jane is the model of an expert patient, with considerable insight and self-awareness, one who takes the initiative managing her condition, in a responsible fashion. It’s a shame that our lack of scientific knowledge involves far more risk than we should have to take, but the shame is on the authorities, not Jane. She is commendably doing the best she can.

Once again, please do not interpret this piece as an endorsement of medical marijuana for treating bipolar. As with any agent used for medical purposes - pharma or natural - marijuana isn’t for everyone and clearly carries risks. In the meantime, I love happy (if conditional) endings. Jane concludes: “For now I feel pretty normal, I'm happy to say.”

July 5, 2016

NEW!

Follow me on the road. Check out my New Heart, New Start blog.