Famous People

VINCENT AND ME

VINCENT AND ME

Reflections on the artist and his madness.

by John McManamy

Reflections on the artist and his madness.

by John McManamy

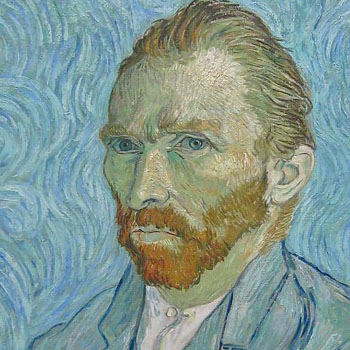

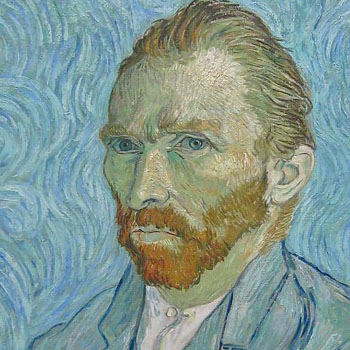

THE IMAGE IS HAUNTING - the sharp nose and sunken cheeks, the desperate eyes peering from hollowed sockets. Face and beard are slashed by violent almost bloody diagonal strokes that clash with the blues elsewhere on the canvas. We have seen the image a thousand times and we know it as the portrait of genius and madness.

His name is Vincent Van Gogh. It was mania that throttled his creative engine and depression or or some other form of madness that extinguished it.

"Well, my own work," he wrote in his last letter to his brother Theo, "I am risking my life for it, and my reason has half foundered."

Six days later, he would be dead, a bullet to his chest, an act of suicide.

In the late 1980s the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York staged a monumental exhibit of the last three years of his life, that extraordinarily productive time when he painted outdoors under the brilliant skies at Arles and Saint Remy in Provence in the south of France.

"There is a sun," he wrote to his brother Theo, "a light that for want of a better word I can only call yellow, pale sulphur yellow, pale golden citron. How lovely yellow is!"

One hundred and eighty-nine paintings he executed in one incredibly manic twelve-month run: haystacks, harvests, cafes, portraits, self-portraits - all these works he poured his soul - and ultimately his sanity - into, which only stood in mockery to his extraordinary gift, without a single buyer to be had.

Think: If you were possessed of the talent of Van Gogh and no one on this planet recognized it, wouldn't you, too, go mad?

For several years now, he had been reduced to living on the charity of his brother Theo, hoping against hope that one day he would find a market for his work.

"What am I in the eyes of most people," he wrote his brother not long after embarking on his career in painting in 1882, "a nonentity, an eccentric, or an unpleasant person - somebody who has no position in society and will never have; in short, the lowest of the low."

Then he added: "All right, then - even if that were absolutely true, then I should one day like to show by my work what such an eccentric, such a nobody, has in his heart."

They came out by the thousands in the bitter damp cold of a New York winter to witness the heart of this eccentric. You had to buy your tickets well in advance. You waited out on the steps, jockeying for a place in the crowd, stamping your feet to keep warm. Then they opened the doors and in you went. You literally ran through the first gallery so as to break free from the mobs, and there you stood in an empty gallery.

You looked at the walls and your jaw dropped.

You ran into another empty gallery, and another ...

And there it was: "Crows in the Wheatfields."

The psycho-critics have had a field day with this one. Flashback to his going after fellow painter Gauguin with a razor, and how he ended up instead deliberately slicing nearly his entire ear.

In May of 1889 he entered the asylum at Saint Remy de Provence. "As for me, my health is good," he wrote his brother Theo, "and as for my brain, that will be, let us hope, a matter of time and patience."

Then it was back to painting, 143 in a turbulent twelve-month stretch in which he would alternately descend into madness and attempted suicide then return to complete some of the most life-affirming works ever to grace this civilization, masterpieces such as "Cypresses" and "Starry Night," with light and form competing in glorious whirlpools of thick bold impasto.

Then there was "Crows in the Wheatfields," his final opus. Even Van Gogh acknowledged the work was an expression of "sadness and extreme solitude."

And I had ten or fifteen seconds of the painting to myself before the vast herds came thundering through. Just me and his saddest work, all to myself, for ten or fifteen precious seconds.

There was that little bit of sky pressing down on the fields, as if of a heavier substance than earth, and there were the fields trying to crowd the sky out of the canvas, as if vaster than the heavens. And there were the crows, hedging their bets, represented by stark black flicks.

There were no two ways about it. It wasn't just a landscape. It was a picture of Van Gogh's horribly bleak world closing in on him. Even as the wheat rose high and the sun shone hot and bright, one couldn't help but gaze into that canvas and feel night falling.

"I generally try to be fairly cheerful," he wrote his brother Theo, "but my life is also threatened at the very root, and my steps are also wavering."

SIGN UP FOR MY FREE EMAIL NEWSLETTER

Even then, in the last two months of his life - now north of Paris to be near Theo - he managed to complete 80 canvases. Then night would fall for good. One day he went out for a walk, and shot himself in the chest with a pistol, then managed to stagger home to his bed. Theo was sent for, and he climbed in bed alongside his beloved brother and cradled his head in his arms.

"I wish I could pass away like this," Vincent told his brother, apparently feeling an inner peace he had never known. Minutes later he got his wish. He was 37.

Some have speculated that genius is fired by madness. I do not wish to get into that debate. Sure, it is most likely that the manic phase of his illness provided the power surge he needed to complete an incredible 400 or so paintings in the last three years of his life. But that same madness also brought his work to a complete stop, first temporarily, then permanently.

The painting would stop. There would be no more Van Goghs.

The gallery was now filling up with people, all drawn into "Crows in the Wheatfields," that foreboding testimony of one's tormented brain in the process of giving up hope.

I had no place else to go, no other gallery to duck into to stay ahead of the crowd, no more Van Goghs. The Van Goghs had stopped. One bright summer day in July, he simply stopped making them.

And I still get all sad just thinking about it.

Reviewed July 15, 2016

NEW!

Follow me on the road. Check out my New Heart, New Start blog.

MORE ARTICLES ON McMAN

MORE ARTICLES ON McMAN

FEATURED VIDEOS

FEATURED VIDEOS